Navigating Card Game Math

Some basic ideas about taming card chaos.

Imagination

The fantasy theme prevails in board game graphics, and I appreciate it in some regards but depreciate it in others. In particular, fantasy graphics don’t provide information, and in games already overloaded with information such graphics don’t make the game easier to play or understand.

I admit I’m more attracted to resolving complexity than getting intoxicated by the narrative. There are psychological reasons that sexy, fearful, idyllic, and threatening graphics enhance the game’s atmosphere. Those reasons provide a reason for these graphics. They enhance the experience but do they make the game better? I guess that’s up to the player.

I’ve always been an overachiever. I’m not satisfied with flashy graphics, I find them disappointing. They might be enough if you’re satisfied with the thrill of imagination but I’ve always been the type who lusts for experience. So when it comes to games, the personal experience is the puzzle itself. I want all the complexity I can handle and all the clarity I can get.

Chaos

For all intents and purposes, chaos equals randomness. The difference is that chaos feels like order that’s out of control, while randomness is just dust. Random things that don’t involve decisions are a bore: roulette wheels, bingo numbers, and lottery tickets offer me no thrill.

I’m fascinated that some people are not only attracted to these entirely random systems, but are addicted to them. Beyond that, as a psychotherapist, I have clients who think they can influence these systems using their minds using telepathy and telekinesis. We say this is crazy, but many sane people feel a similiar form of connection. Some call it luck, others call it insight. People seem to think that if they feel something strongly enough then it’s real. Do you?

Cards

Card games are a tease between chaos and insight. If you know the cards well enough you can overcome some of the chaos. You can count cards, watch others play their cards, and get a sense of the odds for any hand. And then, with every new set of cards dealt, your insights are washed away.

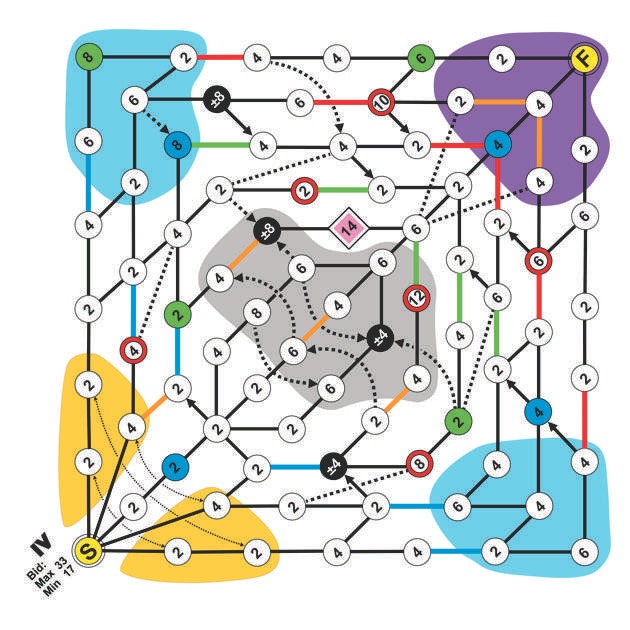

My game Clients Versus Architects combines mazes and hands of cards. The mazes are more like labyrinths. The difference is that you cannot see the way out of a maze, but you can see the path through a labyrinth. It would be more correct to say Clients Versus Architects is a labryinth game because the boards, which are the labyrinths, clearly show all paths through them.

The game is about maximizing benefit and minimizing cost through each labyrinth. What is unclear is the cost and benefit of the many paths. The uncertainty that you’re playing against lies in the cards in each players’ hand.

The Graphical Interface

In Clients Versus Architects each segment of each of the paths through the labyrinths have costs and benefits that are raised and lowered by the cards you play. Because there are so many possiblities, the last thing I wanted to do in game design was to clutter up the images with fantasy graphics.

Instead, I prefer explanitory graphics. As a former designer of Apple Macintosh Graphical User Interfaces, I feel the interface should explain itself. It should not require the user to memorize the instruction manual.

Games, like interfaces, that require study to use are clearly limited in what they can accomplish. My interface, which is my game, is spare. I try not to employ graphics that aren’t explanatory.

The Math

I’ve gotten to the end of this post without saying a thing about math because math itself is not important. What’s important is balance, engagement, and the arc of the game. The math should be felt and not seen.

In Clients Versus Architects, the math is hidden in the cards. The cards feel familiar, comprising four suites of 15 cards each but, as hardboiled card players know, the statistics of the deck is a bottomless pit of combinations.

In Clients Versus Architects there are big and small rewards and big and small obstacles. One designs the game so that the big events correspond to the rare combinations while the smaller events are linked to the likely combinations.

The combinations we’re talking about are runs, straights, flushes, and full houses, traditional poker terms for combinations of cards. At the simplest, there’s the chance of getting one card in a deck of 60 where each person has a hand of 6. But even here, at the simplest, the odds are not so simple.

The chances of one card out of 60 is 1/60, but if you’ve got a hand of 6 cards, then you have to add the odds for all the cards you’ve drawn. For the second draw your chance of getting one particular card is 1/59 assuming there are 59 cards left. But if there are four players each being dealt a card, they there will only be 56 cards left after the first have been dealt. So your chance of getting the one card on the second deal is 1/56.

On the third deal, in a table of four players, your chance of getting the one card is 1/52. For the fourth, fifth, and sixth deals your chances are 1/48, 1/44, and 1/40. So your total chance of getting that one card in the first deal of 6 cards to 4 players is this sum of 1/60+1/56+1/52+1/48+1/44+1/40=0.122. This means you have about a 12% chance of getting any one card drawn from the full deck with 6 tries.

The number is not exact because it assumes that card you want remains in the deck as the draws proceed. But the card you want could have been dealt to another player, in which case your chance of getting the one card does not increase as the draw pile gets smaller.

This is the absolute simplest calculation, but it’s useful. There are certain paths and rewards in my game that I want to make available at the 12% level, and for these I simply need to list this power on one of the cards.

I can extend this statistic by asking what’s the chance of drawing a card of a particular number from any of the four suits? The chance of that is 4x the chance of drawing a card from only one of the 4 suits, namely 4 x 12%=48%.

This number looks too large since each suit has 15 cards and we’re trying to draw a particular one. But the number grows because we’re drawing 6 times. However, the error of assuming the card is still in the draw pile also grows. Still, some number is better than no number and the final proof is in the pudding. “The pudding” is how well the game plays.

The Game Plays Well

This is enough to give you a sense of how statistics are used in the game dynamic. I matched the chances of drawing varous combinations to what gains and losses I wanted as the game progressed. The arc of the gameplay means the greatest rewards and losses should occur at mid-game.

There should still be a chance of a reversal of fortune at the end of the game, but it should get increasingly remote. You want the leader to be rewarded for their skill, but not always. To keep the game interesting you want some chance for an upset victory.

This means that the upset rewards are placed at the end of the game, and the chance of winning the upset reward is much less likely. Some of this can be calculated but, in a chaotic game like Clients Versus Architects, many outcomes cannot be foreseen.

This is what makes the game fun. Not only can’t the players predict the outcome with any certainty, but neither can the game designer. And while more predictablity is good, a certain amount of outlandish unlikelyhood is good too!

To subscribe for more information on the game, when the campaign will start, and special campaign offers to email list subscribers, enter your email here: